“Remember that you are dust, and to dust you shall return.”

So we are reminded every Ash Wednesday. So Adam was reminded as he left the Garden of Eden, following his failed attempt to become like God by means of his own grasping and striving (Genesis 3:19).

God had created Adam from the dust of the earth, breathing life into him (Genesis 2:7). God had invited Adam and Eve to depend upon him for life and every other blessing. That dependence allowed a level of intimacy and joyful connectedness that the devil simply could not stand. From his envy and malice he viciously attacked, by means of subtle seduction. He pretended to offer what God had already planned and desired to give – to share ever more fully in His Glory.

Remember.

Remember who you are. You are dust. You came from the soil of the earth and will return to it. This world and all its desires are passing away (1 John 2:17).

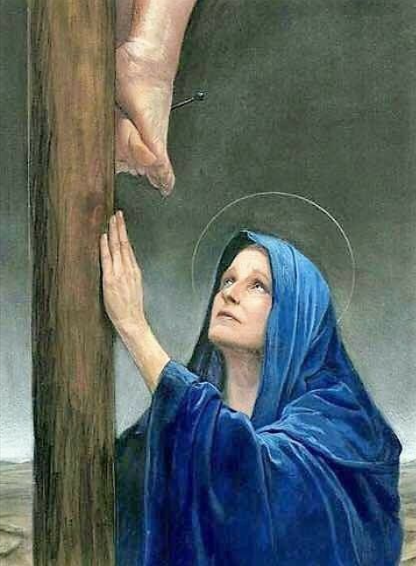

Remember also that you are destined for Glory. Lent leads us to the rescue and deliverance experienced in the Passover of Jesus’ Passion and Resurrection.

We ache for so much more. Every human heart knows the longing, even if it is buried beneath layers of busyness, rugged survival, or mindless distractions. The desires of this world may be passing away, but we remain image bearers with an insatiable desire to return to our true home.

If you’re looking for an early Lenten read, the first chapter of Erik Varden’s The Shattering of Loneliness is breathtaking. You will be in good company, because Pope Leo has invited Varden to offer a Lenten retreat to him and the other workers in the Vatican from February 22 to 27. I was thrilled when I learned that. During these modern centuries in which many in the Church have forgotten what it means to be human, Varden is a voice crying out in the desert, inviting us to remember who we are.

Drawing from the desert fathers, he describes the painful nostalgia we experience, if we are bold enough to let ourselves feel it: “homesick for a land I recall, but have not seen.”

I remember how I began to experience that nostalgic ache with intensity after I had allowed myself to seek help and healing, beginning nine years ago. I stumbled onto the Welsh word hiraeth, and immediately resonated. There are parallel words in many languages, in which homesick humans attempt to describe this wistful longing within: saudade in French, Sehnsucht in German, banzo in Portuguese, Yūgen in Japanese, and many more.

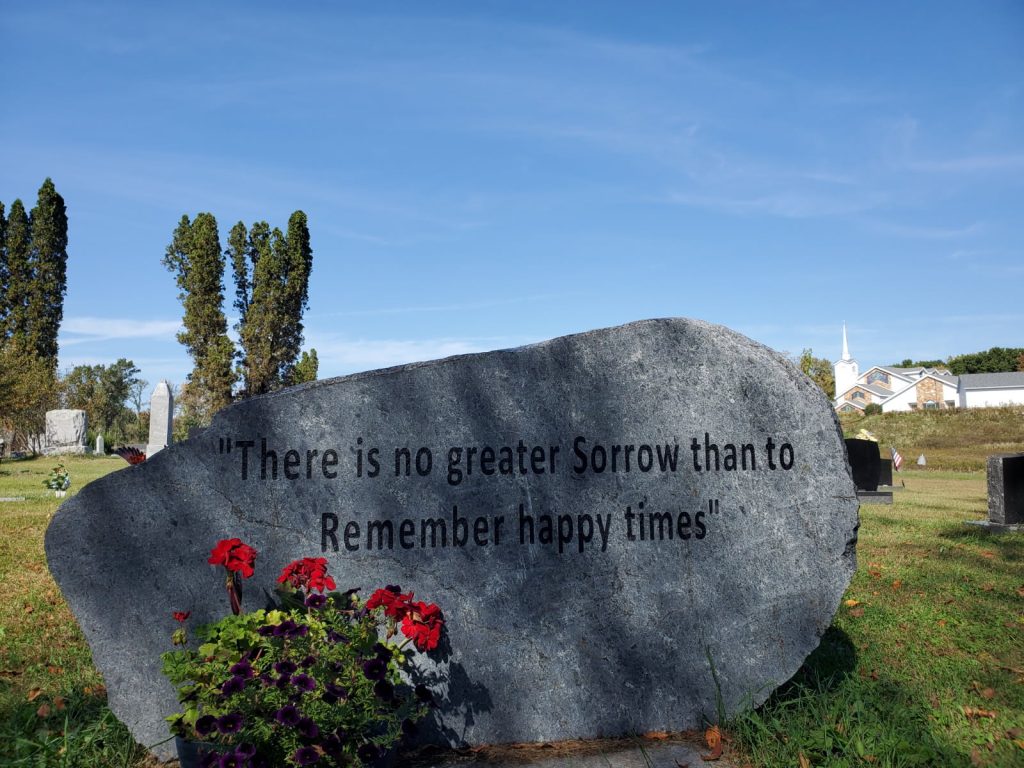

This fall, I visited the cemetery in my former parish. I tend to weep there as I remember so many beautiful people whom I personally entrusted to the dust of the earth. The grave from one such man, who passed five years ago, bears the inscription, “There is no greater Sorrow than to Remember happy times.”

It is especially in our encounters with beauty that our longing for more is awakened. Even amidst the delight, there can be undercurrents of sadness. It is then that we perceive the enormity of the gap between where we have come from and where we are going.

“I am dust with a nostalgia for glory.” This is the fuller truth of Ash Wednesday, as named by Erik Varden.

We prefer to ignore both sides of this human paradox. We turn instead to our shallow survival strategies, whether we cover our nakedness with feeble fig leaves (Genesis 3:7) or mighty monuments of folly (Genesis 11:4). We pretend that we are not really dust. We create a manageable version of “glory” that we can control. Sooner or later, it all comes tumbling down.

Humility is the answer. The word “humility” comes from humus – the earth or soil or dust from which we are created. Humility grounds us. It allows us to accept both our bodiliness and our profound ache for more.

Humility opens up space for Hope, which is how we abide in the tension. We may be from the soil of the earth, but God has planted a divine seed within us. We would so much rather rid ourselves of the tension!

This urge to escape tension is a potential pitfall amidst the sudden widespread interest in healing. I have met many in healing work who are uncomfortable being present to the pain of others in the messy in-between. They feel an urge to fix or figure out, or to rescue. We can harm others when we do so, leaving them feeling more shame and abandonment in their pain.

As Jake Khym and Bob Schuchts pointed out in a recent podcast episode, healing is not about getting rid of pain (even if it sometimes happens). If that is our goal, we are turning God into a vending machine. Rather, healing is an ongoing encounter with God’s love and truth that brings us to wholeness and communion. Unfortunately, most Christian communities, even in healing ministry, are still more comfortable with spiritual bypassing.

Most of us are familiar with the notion that people turn to perfectionistic striving or to numbing addictions to medicate pain. More particularly, however, it is the vulnerable desire for Glory that we are fleeing. Desire is the most dangerous place in the human heart, often fiercely guarded by shame and contempt. I’m not talking about fleeting earthly desires, but the homesick longing for more. If I let myself feel that longing, I am no longer in control. And what if everyone rejects or abandons me then? It seems far better not to go there – except that this self-protection becomes increasingly exhausting and lonely.

“The Shattering of Loneliness” – what a title for a book! We each experience a desperate loneliness because our trust in God and self and each other has been shattered through betrayal. Through his Passion and Resurrection, Jesus now shatters our loneliness. In our survival outside of Eden, we have been striving to manage and control or to hide and escape. It is once again possible to connect and receive – if we are also willing to wait in Hope.

God so honors us as image bearers that he desires us to grow into His Glory, at our own pace and with our full consent. We need healthy community to do so. Ash Wednesday is a marvelous shared witness to these truths. It’s a truly communal experience. As a priest, I can offer a private Mass, but it would be absurd for me to impose ashes on myself in my private chapel on Ash Wednesday. We witness with each other in God’s presence what it truly means to be called from dust to Glory. We recommit to our shared sojourn through the shadowlands. We rekindle our ache for home.

In the witnessing and connectedness of healthy community, and in being reconnected to the love of our Father, our loneliness is shattered. It’s not that every longing has been totally met. We might actually suffer more in our longing once it’s witnessed – just as poets often feel agonizing desire in the presence of beauty. Some of the holiest disciples I know suffer the most when they feel intensely connected to God. They desire more, and are painfully aware of the gap between human dust and God’s Glory. They are holy because they keep daring to desire, to be known in their desire, and to be stretched in the tension of waiting.

As we receive our ashes this Lent, may we encourage each other in remembering who we are: dust that is called to Glory.