I’ve been appreciating Brené Brown’s newest book (Strong Ground). She names some of the paradoxes that wise and courageous leaders learn to embrace.

I immediately resonated with the chapter on the importance of “negative capability.” It’s a concept she found in a letter from the poet John Keats (1795-1821). Keats praises this capacity that he perceives in great men like Shakespeare – “when a man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.”

There are moments when abiding in love and truth is particularly painful. These are the moments of the in-between, when we have only partial insights or unsatisfactory options. We feel the pressure to make something happen and get away from the tension as soon as possible. It becomes almost unbearable to abide and wait for fuller truth and goodness and beauty to emerge.

To be human in a fallen world is to live in this tension. We are stretched by two seemingly incompatible truths. On one side is the harsh reality of impermanence. As much as we attempt to deny it, our earthly existence is fleeting. Nothing gold can stay. On the other side is the nonstop human tendency for meaning-making. We insatiably interpret what is happening and why – a task that our brains engage both consciously and unconsciously, even while we sleep! We don’t like waiting to receive the fuller truth. We both desire and need to belong securely and trustingly to something solid.

To put the paradox differently, our human hearts were not created for endings, and everything good in this world comes to an end. What can we do?

As Brené Brown puts it, “Negative capability is a difficult muscle to build. We’re wired to resolve tension and seek certainty. This capability requires the ability to reach inward toward stillness rather than out toward counterfeit facts and reason.”

“Be still, and know that I am God” (Psalm 46:10).

Even in turning to God, we are likely – in our urge to escape the pain of this paradox – to engage in yet another form of irritable grasping or controlling in the face of eternal mysteries that are never for sale, and will repel any attempts as seizing or sieging.

I’ve been reading the comments of a few thousand participants in the listening sessions I facilitated for my diocese this fall. You can feel attempts at grasping among many of our longtime parishioners who (in a world where everything has changed so much and so rapidly) expect their parish church to be the one place where nothing changes – only it already has, many times over. You can feel the grasping in the comments of hundreds of others who expect everyone else to adopt their political or liturgical ideology. If only we all thought this way, or all did things this way, our pain and suffering would go away. They forget the flaming sword that will not permit us to return to Eden (Genesis 3:24).

I empathize with their fear and restlessness because I know those movements in my own heart! I have my own versions of grasping or striving or hiding when the tension feels unbearable.

The real invitation is go deeper into the paradox without trying to escape it, nor to escape the tension found therein. This is exactly what Jesus and Mary do on Good Friday and Holy Saturday.

Jesus, true God and true man, does not erase or eliminate the dreadful consequences of our human freedom. Rather, he brings eternal love into the depths of our humanity, loves us to the end, and invites us back into relationship – with his Father and with each other.

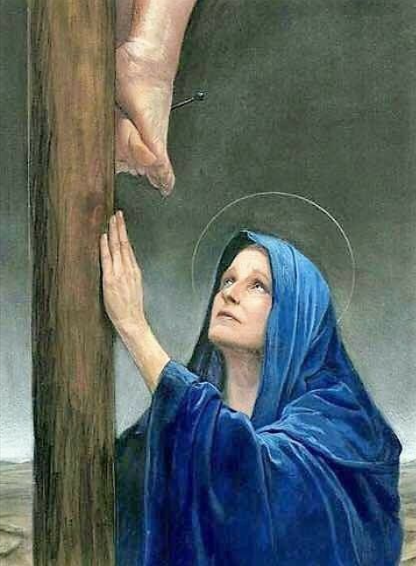

His mother Mary does not do what so many churchgoers do when feeling the powerlessness of this paradox. She offers no fixing, no advice, no comparisons with others who have it worse, no backing away from his Cross. She stands with and witnesses.

Her with-ness and witness continue on Holy Saturday, a day of Sabbath – a day of stillness and rest. “Be still, and know that I am God” – these words sound so pleasant and peaceful in other settings. Not so much on a day of Sabbath rest in which your Son is buried in the tomb, and you are utterly powerless. Even then, rather than grasping or escaping, Mary embraces the promises of Jesus and waits in Hope amidst the paradox, not knowing how he will fulfill these promises until it actually happens.

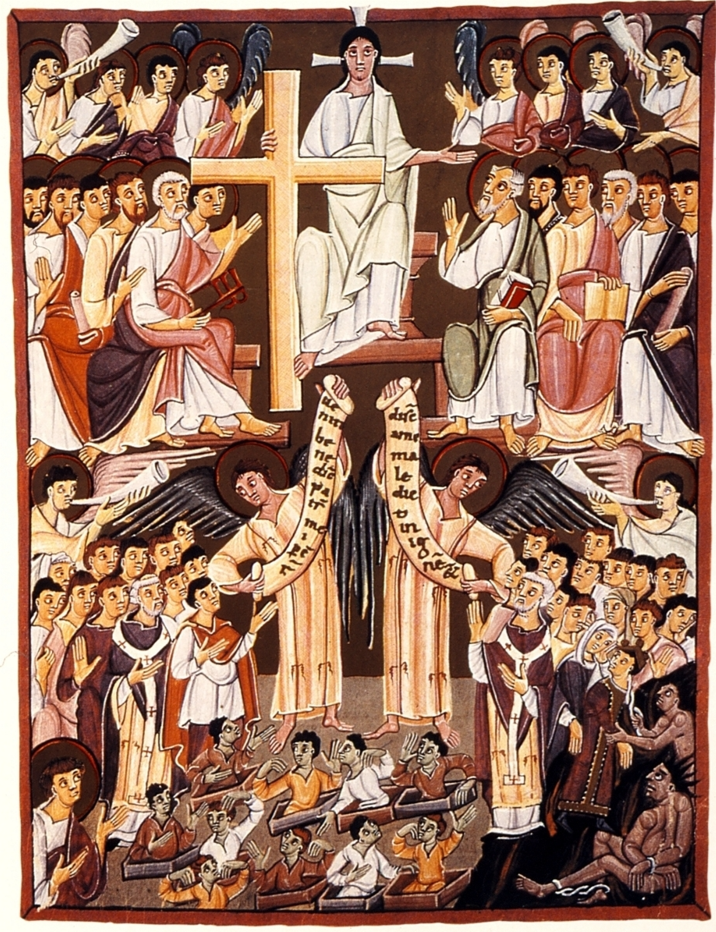

Even after the Resurrection and Ascension, when so many questions remain unanswered, when the disciples are still downcast and doubtful, she abides with them and prays with them for nine days (Acts 1:10-14). They learn from her the capacity for passion and compassion that she exhibited so beautifully at each earlier moment of her discipleship, a capacity which grew and deepened as each mystery unfolded.

Yes, prayer and liturgy and Church are all part of our human response to this painful paradox – not so much being the answer itself, but the context in which The Answer can be encountered, again and again, stretching our capacity to receive – which also means stretching our capacity to suffer! The suffering of the Saints does not diminish as they grow closer to God. The greater their longing, the greater the gap feels between them and the living God. The greater their willingness to stay connected to others, the greater their capacity to suffer with. Show me even a few such saints, and I’ll show you a church community that is thriving on mission!

I find Brené Brown’s words both comforting and emboldening: “Resist the urge to reach for certainty where it does not exist. The longer we can hold that paradox, the greater our capacity to see and honor one another in our fullness AND in our contradictions.”

Faith and Christian community are essential, not as an escape from the tension of this world, but as a shared receptivity of the eternal, and of the mystery of each human person. It is in abiding relationship and receptivity that we can glimpse and taste the goodness of the Kingdom of God, and can persevere in our sojourning until this world definitively passes away, when Jesus comes again with full righteousness, wiping every tear away and abolishing death forever.